This is a story like no other; one of courage, bravery and determination. Paul Nealon was in an accident that threatened his ability to ever walk or move again. Several doctors told him the odds of him walking again were extremely low. However, that didn’t stop him; with a lot of hard work and determination, he was able to start moving again. This is a story that is sure to inspire many and make listeners feel like nothing is impossible. This episode also drives home the very important message that no matter what anyone tells you, only you know what you’re capable of. Paul Nealon is truly one of a kind and the perfect example of tapping into unlimited potential. Once you start listening, you won’t want to stop! This is a must listen, and 2logical’s first official “interview format” episode! Be sure to check it out, and check us out on social media and let us know what you’d like to hear next!

Want to talk with Paul?

If you or someone you know has a disability, Paul has graciously offered his help, perspective and wisdom. Send us an email at info@2logical.com with your story, and we would be happy to put you in touch.

Listen here: Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Anchor / Stitcher

Shownotes

0:46- Intro

3:23- What is a culture of innovation?

8:43- Why it is important to instill a culture of innovation in the workplace

10:46- We are all apart of many different cultures

13:14- Why it is harmful to believe that you aren’t good with innovation or change

14:23- What are the harmful beliefs about innovation and change that people should look out for?

18:54- What are the barriers?

23:42- How to go about “rebranding” yourself

26:47- Create a “no complaints without suggestions” approach

37:16- Let others speak first

38:59- How to become more resilient individually and at work

45:02- Goals are important!

50:49- How to instill courage in others

52:06- Get rid of negative thoughts in order to succeed

53:58- How we communicate with ourselves & why it is important

1:05:56- Conclusion

Transcribed Audio

David Naylor: Well, hello everybody. Welcome to this edition of The Motivational Intelligence Podcast. We have a very, very cool conversation today. We’re very fortunate to have Paul Nealon here with us, and Paul is a wonderful gentleman who I’ve known for, geez, Paul, how long do you think its been now?

Paul Nealon: Well, it was before you got married, Dave. When you guys were over at Midtown. Before you and Michelle got married.

The handsome couple, you know, he’s got a beautiful wife too, and he’s a good, handsome guy, walking around and, my kids would go, “Who’s that guy over there?” So, you know, Claudia and I both, we got to know you kind of peripherally, if you will.

It just kind of went from there. And you know, we see each other off and on. And we even had cars that were very similar, even though yours was more expensive. Your beautiful convertible. Then he goes out and gets that other sports car.

David Naylor: Yeah, no, I sold that one. It’s been a little bit of my affliction, the automobiles over the years. But the nice thing is it’s something that my son is very passionate about as well. So it’s been one of those things where it kind of pulls the two of us together.

Paul Nealon: Go out and around a bit.

David Naylor: So the cars and the motorcycles are the common point.

Paul Nealon: You’ve got motorcycles, too? So that wouldn’t go over well with my wife, my oldest one down in Austin, he has a motorcycle and we just found out about it. My wife went off the wall. Yeah. But she was not happy about it and he goes “I’m not getting rid of it.”

David Naylor: I grew up with them and my father, I bought my first street bike when I was in college and I thought my father was going to disown me. He was not happy about it either. And then he accepted it and Ben’s grown up with them. So it’s just been something that we’ve kind of had together ever since.

Paul Nealon: Does Michelle ride them?

David Naylor: She rides with me or rode with me before we had kids. Not since. But she has talked about getting one once the kids get settled and stuff like that. So yeah, maybe, down the road, we’ll see.

Paul Nealon: So Ben gets replaced.

David Naylor: Mom bumps them out of the way, right?

Paul Nealon: Now you’ve got to hang around with her more often. It’s like, you know, that’ll be okay. You got to do something.

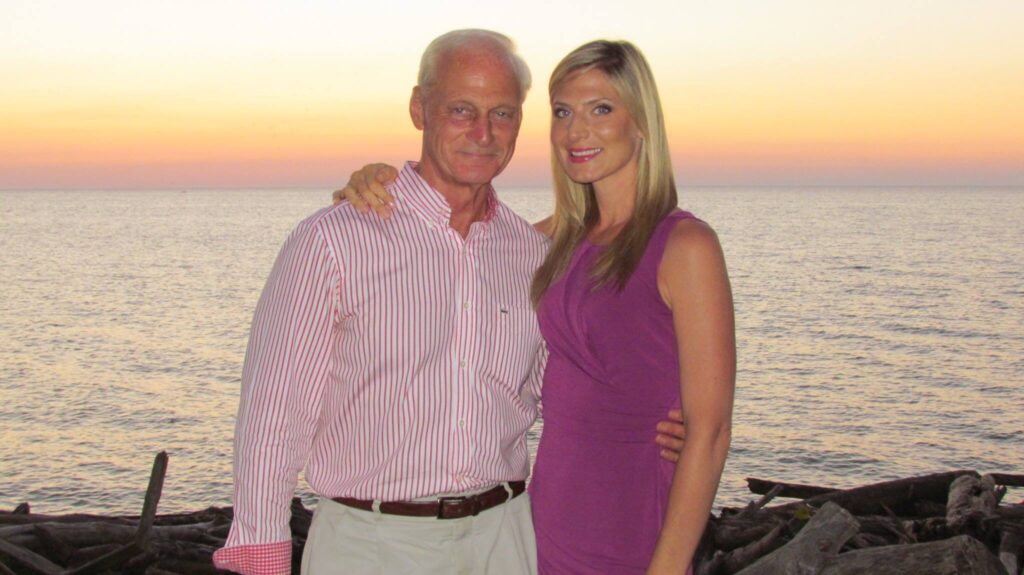

David Naylor: So, Paul and I have known each other approaching 30 years, met through the gym and Paul is one of these guys that in fact, I was telling Sean this story yesterday, when you meet people, one of the things that helps remember names is you kind of do word association and things like that. So, my association for you was Paul Bunyan. You’re a big, handsome guy, in good shape, so every time I remember seeing you all those years ago, I go, “Oh, there’s Paul Bunyan.”

Paul Nealon: So now because I’m bald and all that happy stuff, and I used to have a mustache and stuff like that, a lot of people knew me as the Hulk. They called me The Hulk. And I actually kind of look like The Hulk when my hair was longer on the back and I had a little bit more hair back and it was kind of funny.

People would either call me The Hulk and somebody just a couple of weeks ago said that to me. They said, “You look like Hulk Hogan,” and I go “Even without mustache?” And I’m thinking to myself Hulk Hogan is huge, as you know. And this was a couple of weeks ago and, well maybe my body’s coming back a little bit from where it was, from where it was two years ago, if you saw me two years ago. Sean, that’s a whole different story. When was the last time you saw me, would it be about a year ago or..?

David Naylor: When you came back into the gym? It was probably about a year ago.

Paul Nealon: Alright. So I’ve added a little bit, my definition and stuff is coming back. I’m at about 60%, somewhere around there, at least, I think 60%. I’m going to 105%. I told you that before. I’m coming to 105%, the other 5% extra is about the mental side that I’m trying to work on right now. How do we improve the mental side of things and give back to what I’ve been given over the last two years and where I’m going to carry this, but where does it go? I don’t know, but, we’re going to do something with it.

David Naylor: Well, it is a pretty magnificent journey over the last couple of years. We’ll, we’ll dive into that a little bit. So Paul, share with us a little bit, kind of about your upbringing. Did you grow up here in Rochester?

Paul Nealon: Yep,grew up here in Rochester, born and raised in the Rochester area. Grew up in Greece, New York, if you will. My parents purchased a home in back in 1949, 50. I was born in 50, so that makes me just about 69, a little over 69 years old.

So, went to St John’s Catholic school and Greece, and I went to Cardinal Mooney for four went on to a MCC, did two years there and thought,” Oh God, I only need to do two years of college, I’ll be fine.” I found pretty good jobs and everything worked out very well.

And then I went over to Eastman Kodak and got hired there, but not at the job level that I wanted. And they paid for school. And it was like, here’s an opportunity. Now go back a little bit further in my past, I come from a family of eight kids. So I’m one really one of eight, third one and I had two older brothers, so, hand me downs were a thing that occurred just about every year as we grew into our, my parents, my dad worked at the post office, my mom was homemaker. Back at that time, most mothers were homemakers. They didn’t work out of the house.

She had her hands full. And so, going to Catholic school that was a little extra, additional cost to them. You had to pay for schooling for each of us. We all had to wear ties and shirts and special pants and all that stuff. So, to afford that was not easy for them.

They were very hardworking. My mom always made sure that our clothes were clean. They may not be the newest, but they were clean. My dad just went to work every day and every time he had a chance to work overtime, he worked over time. And so I learned a great ethic as far as work is concerned and just keeping your head down and try to be a good person.

That basically was the way I was brought on. It was just shown through, just by seeing what’s going on and how to deal with people. My dad was kind of an introverted person. He kept to himself and just family man, top to bottom. I can’t say enough about him.

He always says, “I wish I could have given you more. I wish I could’ve done more.” He gave me a whole lot. I’m very fortunate and my mom and dad have known each other, I think since first or second grade. Wow. And so they are both 97 years old now.

They’re coming up, I think on their 75th anniversary. So it’s kind of cool that, you look at that and go, well, if I didn’t keep falling off ladders and having things happen to me, my longevity might be, um, a little bit longer, and I’m trying to make it longer now, but I keep doing dumb things.

David Naylor: Well, you got the good genetics. That’s a good thing!

Paul Nealon: My parents really, you know, from there it was like, okay, you learn one thing: there’s no free lunch and you’ve got to go out and you’ve got to earn what you’re going to get, and if you don’t have it, first of all, there’s the embarrassment of not having anything.

I say that and if my parents heard this they’d probably say, “Well, how could you say that, Paul?” They gave me everything they could. They gave me the ethics, the morals, that type of thing, the good education. But as far as extra stuff it was like, back in the day when you could pick up a bottle and bring it back to the store, and if you had a day where, I don’t know if you remember that, Sean, you probably don’t, but you could pick up a bottle and take it back to the store and they would give you 2 cents for it.

That’s how I would pick up 10 cents though, to buy a Coke, something like that. There wasn’t a, McDonald’s, it was called Carol’s at the time. So, you know, if you wanted to go down to buy a 12 cent hamburger, that’s 12 cents for a hamburger.

You know, I feel like I’m talking like my grandma. You know, the grandmothers, “I remember back when butter was only a nickel.” So here we are, 12 cent hamburger. But you learn, going back to my point around, you learn that you’ve got to do it on your own.

So, I did the paper routes with my brothers, morning and night, paid for my schooling. Put myself through, and I actually paid for Mooney. I really, yeah. Then I paid for MCC and I was basically told at that time I wanted to go off to some other colleges and basically was told, guess what?

It’s not there. I decided that I was going to go to MCC. And so that’s what we did. Yeah. And I took a marketing. I love marketing, I love advertising and whole thing, but got into the business side, started working on that. Before I know it, I finished my two year degree and I think I finished with a math major as well as a marketing major. Then I decided, like I said, “Guess what? I don’t need any more school.” So I go over work for this company. I went over to Eastman Kodak and started working there. And like I said, then finished out at R I T night school.

That went on for about six years, and finally got that. As a result of that, was promoted many times. And so everything went very well. And then I moved down to Johnson and Johnson, was a director of procurement or supply chain, as they call it now. Then I moved down to Harris RF Communications and I was there for 12 years, I believe, after that. So again, in supply chain, international materials and things like that, was able to travel the world a little bit, see it, learn about other people. Everybody come to find out is pretty much the same. We all have the same problems.

If we have children, we worry about them, we take care of them. We try to get ahead and then we try to get home and see if we can have some playtime. And that’s kind of where we go. So, in a nutshell, that’s kind of who I am, how I got to be where I am before my little accident.

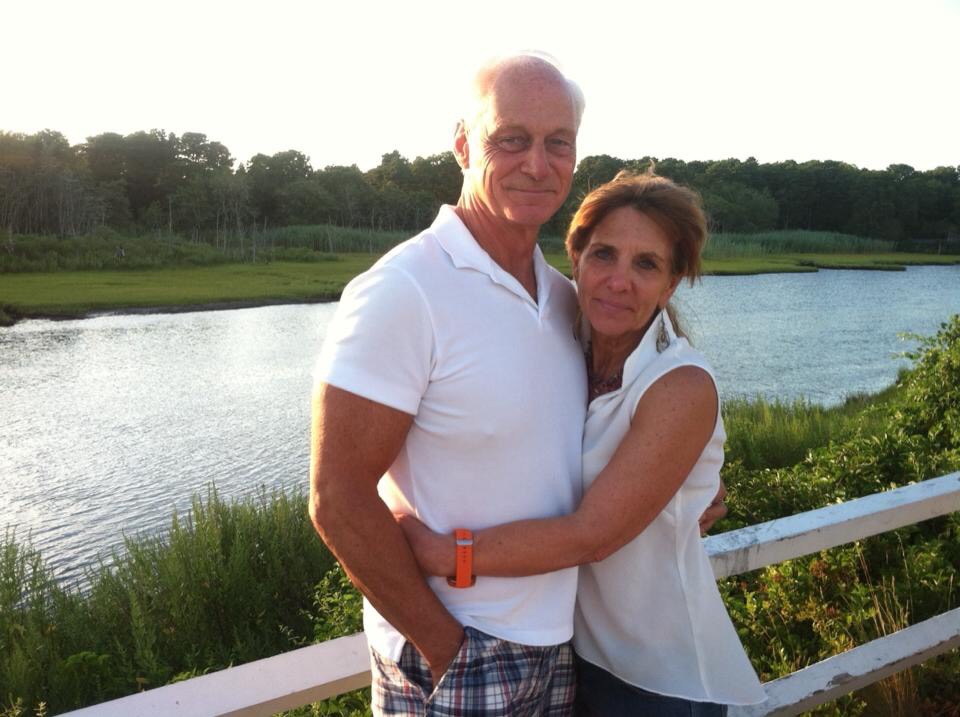

David Naylor: So you’ve been married to Claudia for 40 plus years now

Paul Nealon: It’s coming up, 38 years. Okay. We’ve been together for, add another nine. So that’s 47 years. I kind of tried to get away several times. Went out for almost nine years ago. I was like “I’m going to escape,” but no, I never did go, which was very fortunate, on my part. I just didn’t realize what I had at the time, so I do now.

David Naylor: Smart guys always marry up.

Paul Nealon: Yeah. Big time.

David Naylor: Smart guys and guys who can sell, always marry out of their league, you know?

Paul Nealon: Absolutely. Yeah, that’s true.

David Naylor: So, you know, three kids, you had a successful career, retire, and then May 20th, 2017 happens, so walk us through, cause there was a major life shift there. So tell us a little bit about that day.

Paul Nealon: Well, I got up. Its a Saturday. It May 20th, Saturday, it’s probably about 8:30 and I always go to the gym at 9:30/10 and I’d get home by 11/1130, and I tried to get two hours, two and a half hours in. So I got over there probably about 9/9:15.

Did my workout, weighed myself, everything. I hit all the things I wanted to do. That was a great workout. I was thinking about getting home and taking care of some things in the backyard, and, it was like, okay. So I got home about 1130, and I dropped my gym bag and head back into the garage and grab that ladder and , think about, okay, how are we gonna set it up, blah, blah, blah. And then I grabbed the saw off the garage wall that I have hanging there and head out to the backyard, set it up on the tree. I’m looking at this little limb that happens to be, oh, about 10, 15 feet off the ground.

It’s in my neighbor’s yard. But it’s blocking some sunlight that’s going onto my pool and I have to have all the sun that I can get, right? So I line up the ladder and I didn’t even have, it was one of the extension ladders, but I didn’t have to extend it. It was, you know, 20 foot or the one that goes up to one 40.

And so I just leaned it up against the tree and made sure it was stable. I had to actually lay it across the, now if you have mentioned there’s a stockade fence between my neighbor’s yard and my yard. So I had to take the foot of the ladder and lean that out over the stockade fence up against the tree on the other side, and I climb right up.

I made sure it was stable, I thought. And I bring my saw up there and I’m only up about, let’s see, the ladder was 20 feet. I’m up about 14 feet. Okay. And I reach out, the limbs right there. It’s a little three-inch limb. It’s just hanging out there, about eight inch or eight feet or so.

And I push once, pushed twice, push three times, on the fourth one as I’m lunging too because of the branches on the side of the tree. I’d lunge and the branch cut through and the ladder gives way, because by lunging, I didn’t realize it was gonna break through on a fourth one. If you were cut.

I go out and that whole ladder gives way at the bottom. And it catapults over the stockade fence. I’m heading down on the other side. And my arm, my left arm gets caught a bit on the ladder and my right arm is tossing the saw out to the up to my right. So I don’t come down on it.

You know, I’m thinking that’s all real brilliant. Now this is all happening within a second or two, right? And now if you can imagine, I’m heading out. My head is coming now down straight towards the ground. My whole body is going to be impacted. My neck is impacted by the weight of my body, and I had no way of breaking my fall.

My arms are off to the side. And so when I hit, I hear the crunch. I knew immediately, I didn’t lose consciousness. I immediately knew I was paralyzed. The first thing that hit me was a thought about a kid who swam or dove into a pool.

He went to McQuaid high school and I don’t even know the kid’s name, but I don’t know what made me think of it, but it was story that we had heard that in the past and that this gentleman, young boy, was a quadriplegic as a result. And I don’t know anything more today, but that’s what hit me right at that second.

And it was like, “Oh, no, I’m that person.” Then the follow on second was I asked myself, “Why me? Why me? And the weirdest thing came back was, and I’m not a religious person, but the answer was, why not you?” It’s the realization that, what makes you think that you are so immune to everything and everybody and everybody else gets affected.

My legs are over my shoulders, my face is looking through my groin and I’m upside down. This is all going through my head and a minute now has gone by and it’s dead quiet. It’s a beautiful sunny day, its probably 11:35, 11:45 at the time.

I’m sitting there on the other side, sitting there, laying there upside down, trying to figure out how can I yell, help. And as I said, okay, I’ll just yell help. I’m so rolled up, I can’t get any air in my lungs to blow that out. Right. And so all I go, help (softly) that’s all I could hear.

Now it’s like, this isn’t going to get you where you need to be, you know? And, So with them. So its been about a minute or so, this person comes walking up and says, “Hi, I’m Sylvia. Can I help you?”

David Naylor: Wow.

Paul Nealon: And I’m looking at Sylvia, who I’ve never seen in my life. And she’s upright but I’m upside down from the ground and she’s upside down too. And I said “ hi. Um, can you call 911? I’m paralyzed. I broke my neck.” And she, um, she’s like, “Oh, yeah.” And, well, come to find out, Sylvia is my neighbor, who lives across, a little adjacent to our house across the street and somehow heard the ladder and the commotion. It wasn’t a lot of commotion, you would think “ Oh, you know, okay. Ladder, bang, bang, bang.” There wasn’t any scream. I didn’t yell help or anything like that. So, you would think, um, okay. Nothing much happened. I put it in reverse. I said, “Okay, Paul, if this happened in reverse and something happened over in Sylvia’s yard. What would I do?”

David Naylor: Would you have even noticed?

Paul Nealon: I would’ve said I would’ve gone. “Oh, okay,” I’d listen for another sound or something. I think, well, you know what? Everything must be okay. Yeah. And I would just go on with whatever I was doing.

This young lady had the gumption or the, I don’t even know how to describe it. The ability to walk across the street, to walk into my neighbor’s yard through his weeds and bushes, and it was May, so things were overgrown already and they hadn’t been cut.

She came all the way into this backyard and by this large third tree, elm tree and finds me upside down. I won’t bore you with the whole story, but she called 911, she happened to be a doctor from Strong Hospital. She calls the emergency room, lets them know that they’re going to have somebody coming in very shortly, right. And that they need to have the MRI machine ready. And before she hangs up the phone. And, I hear her get done with U of R , Strong people at emergency and she said “The ambulance should be here soon,” And I said to her.” I can hear it,” in the distance as she was talking, I could hear it coming.

So within, I’m going to say three to five minutes, they show up at our house. And my wife happened to be heading off to a business meeting. She’s in real estate for Remax. And she came out the door in the back and I could hear her say, “Paul, Paul, are you here?”

And Sylvia who, if you can imagine, you’ve got the stockade fence. The Soviets on my side, quality is dying the other side, and I’ve fallen on the other side so she can’t see me. So, she comes and Sylvia says, “He is on this side. He fell off the ladder,” and she could see the ladder. That actually hit catapulted over the stockade fence.

She knew something was wrong. And Sylvia to said, “Hey, the ambulance should be here. Could you go out and meet them?” Claudia did not come around the fence to see me and I’m glad she didn’t. I was rolled up, like I said. They arrived and they came in and they unrolled me.

They put me on the board, put me up on the gurney, rolled me out, and took me in an ambulance. The last thing I remember, are the wheels when they put me in the ambulance. I remember hearing the clunk of the transmission kicking in.

And then the wheels go “roo, roo, roo.” And then I was out. Then all of a sudden I’m at the hospital, which is only about three minutes down Elmwood Avenue. And about three minutes away they shoot me in there and all of a sudden there’s a cop helping take me out of the ambulance and take me in an emergency room.

From there I got to make the phone call to my three kids. My wife, Claudia at the time, had called ahead and had my sister and brother come over. So they came to the emergency and they were around me at the same time.

So, I’m lying there and Claudia says to me, you know, “We’ve got to call the kids and let them know that you got hurt”. And I think she probably knew more about the situation being a nurse, ex nurse, that we needed to make that phone call because we didn’t know where this was going to go.

So we make the phone call and being tough. I didn’t realize how I was affected by making that first conversation with my oldest son, Chris. And guess what? I had to leave a voicemail. All three kids are busy and doing their thing, so, I made all three phone calls, nobody answered the phone.

I just left messages and the message would basically, with tears in my eyes, I basically said, “Hey, I got hurt. I’m going to be fine. I’m in the emergency room, the doctors looking at me and I tried to keep it as upbeat as possible and just not to instill any fear or just, you know, “Hey, we’ll catch up on the the other side.”

Knowing possibly that might be my last conversation, I say, and leaving those words with them and thinking, I just want them to hear my voice, that I love them. That was probably the hardest one. You can see, I got tears in my eyes now. Every time I tell that story, I was living in fear that not that I was going to die, that they were going to have this last message from me, via recording. I didn’t want that to be the case. So that’s kind of where we are.

David Naylor: So, at this point then, the doctors are coming in, they’re trying to diagnose what’s going on. And to give you some kind of a prognosis of, what happens next?

So were they able to take you right into surgery or when the doctors came in and were able to run through things?

Paul Nealon: It actually moved a little bit quicker than we thought. At the time I’m sitting there with Claudia, my brother Bob and my sister, Beth.

I’m laying there and I just finished the phone call and I said to Claudia, “The room is closing down.” If you can think about a lens, just like the cartoons, the old cartoons, where they used to close off at the end? Well, it would close down and all of a sudden the lens kept getting smaller and smaller and smaller.

And I said to Claudia, “Claudia, I can’t see,” and I guess that’s the result of your neck swelling and starting to pinch things off. At least that’s what I’m told. So I’ll take that as an explanation. Claudia said she ran over to the emergency lady and just said, “Listen, you’ve got to get him in.”

They had already called Dr. Molinari, and luckily being one of the best in Rochester, he was supposed to be going to a party or something like that at like one o’clock, I’m told, now I don’t know if I’m making this story up. So having happened before one o’clock, I got one of the best surgeons that can put Humpty Dumpty back together.

So that’s kinda where it ended up. So that’s kinda how, before I knew it, they had me in the MRI machine very quickly. I do remember overhearing the two technicians that were in the room. The one girl, lady, was talking to one of the guys there and they couldn’t figure out why they had two male female plugs, and it was like, well, who’s got the male plug? I don’t know where…I’m thinking this and I’m in it all. Am I making this up? But I’m inside the thing, and I don’t know if you’ve ever had an MRI, but if you are in that tool, you can’t move around and it is very claustrophobic feeling, if you will. So, that’s kind of where I was at that point. I think I lost consciousness and I went into surgery from what I’m told, and that’s kind of all I can tell you until I wake up after the surgery, you know.

David Naylor: So then coming out of the surgery, at that point, after the MRI, they knew what the damage was. So what was the damage that had happened in the neck one as a result of the fall?

Paul Nealon: So, what I’m told and what I was shown was that I had crushed part of my spinal cord between the C two, three, four and five and very, very close to the C one, as many people know it’s kind of immediate death. So my Dr. said, “Guess what? You got within about two hairs of doing damage to C one. And, Claudia, after we saw him, I think it was a while after surgery, I would say my checkup was about five months after, Claudia says to Dr. Molina, we called him Dr. Bob, “Hey, how did Paul get through this?” and he says “First of all, I’d like you to understand that it’s my best surgery I’ve done, if you will. But I could only put him back together as well as I could do. I would love to say he’s walking around and moving because of me. Some of it has to do with me, but I had to put him back together. That’s the best I could do. So the damage, those areas are now fused.” So he did the best he could do. And I’m sitting here, I’m doing what we’re doing today because of him.

David Naylor: So, you come out of the surgery, he’s told you that were literally a hair from dying, but your spinal cord has been damaged, you’ve impacted for different vertebra, so what was the prognosis that they told you when you came out of surgery, what were they telling you your future was going to look like?

Paul Nealon: They basically said, “We’re not telling you anything.” I mean, its like, “We’ll have to see. We think we’ve repaired what we could repair to the mechanical side of it. The rest is what your body allows you to do. The good news is that you had built up your neck very, very much from weightlifting and that type of thing,” so other people may not have, especially my age, and falling, typically would have probably died right there. So it was lucky that I was in good shape at the time. At least that’s what he said.

David Naylor: So, obviously anytime you have an injury, your muscles are gonna atrophy, you’re effectively, you have no sense of sensation, below your neck. So what did they begin to do, coming out of it, or did they take, is there some form of rehab? How did that, that process work?

Paul Nealon: Well, after I gained consciousness, I’ll say a day and a half later, and I was in and out, and I remember seeing people go by my, my door and stuff like that, but I can’t tell you that I was even conscious at the time. I probably lost two days. So if you could imagine it was sad. It happened on a Saturday, finished surgery and all that happy stuff, probably late Saturday night. So we went through Sunday, I think it was Monday I probably was able to, at least blink my eyes and stuff like that. I had a tube down that was intubated for, I think it was three or four days. So just making sure I was breathing and all that. But, beyond that or, I just lost my thought. I’m sorry.

David Naylor: It’s alright, so you’ve come out of surgery two days later, basically. The doctors coming in, they’re telling you, we just don’t know what’s gonna happen from here?

Paul Nealon: Oh, okay, so you got me back in. Thanks. So they came in and they said, “okay, we’re going to move you down to the intensive care unit.” I said, “okay, fine,” you know, what am I going to say about that? They took me down there and um, gave me the option,

“Would you like to have physical therapy and occupational therapy? Would you like to have that one hour a day or four hours, three to four hours a day and well, naturally, you know me, Dave. So I went for the three to four. I got to tell you that it was intensive for them because I couldn’t move my limbs. So they had to move my arms. They had to move my legs and my wife, Claudia…

David Naylor: So let me ask you, Paul. First, you think of a lot of folks who might be in a similar situation who maybe just giving up hope or just saying, “oh, woe is me,” type of thing. You came back and you said, “I want four hours of therapy.” That’s not a normal response.

Paul Nealon: But you know, I work out two hours a day, two and a half hours a day. So it’s like, okay, so it’s just an extra hour. And if it’s going to get me to where I want to be faster, why wouldn’t I do that? As opposed to saying, I didn’t think that was me, I just thought, “how do I do that?” By the way, I didn’t know what I was gonna have to do. And if you can’t move, you really don’t have to do any work, you know? So they said, it’s like, well, somebody else has got to do any work, just move me around.

I mean, I’m literally a baby. If you have a newborn baby who has no muscles, that is conscious of everything that’s going on around you, which is the scariest thing because you’re sitting there going, “I could move a second ago and now I can’t.” No matter how hard I tried to move anything on my body, other than, I can pick my head off the pillow and blow into a tube.

But other than that, I’m not doing a hell of a lot. So I was given those options. So we started doing therapy on that Friday, within six days. And I said, I was doing the therapy, they were doing the therapy. I was blessed to have, we are blessed in Rochester to have such care and such, I mean, the Strong Hospital, Monroe Community Hospital, the Unity Hospital, and the people, I mean, doctors, nurses, assistants, we have people that just take care of us and I’m this little baby that’s being thrown around and wiped and I need everything done for me, everything. It is the most devastating, humiliating, your dignity, is basically thrown away.

You are open to the world if you will, and you are dependent on everything. I could only ask for stuff, blow into a tube and the nurse would come in and, and say, “can I help you?” And it would be, “Can I just have a sip of water?” and the drugs were drying me out and all that. So you know, how do you handle that? I guess I didn’t think about it. You know..

David Naylor: That’s where life is at that stage.

Paul Nealon: It was, I pictured myself at that time, laying in a bed in my sunroom. We have a beautiful sunroom that looks out over the pool, and I’m sitting there thinking “That’s where I’m going to be for a while, and I just don’t know if I can do that.” I can’t possibly imagine my wife taking care of everything I need, laying here the way I am in this state right now. If and when I get out of the hospital, going home and being in that condition and having somebody, it’s unimaginable and I could not fathom it, but I had to at least think about it.

David Naylor: So, you’re in the hospital, four hours a day, you’re occupied with the therapy and those types of things, but you’ve got another 20 hours a day where you’re basically just laying there. How did you occupy your mind? Or how did you keep your yourself focused in some kind of a positive way and not just go crazy?

Paul Nealon: Well, the first couple of days, they were taking me down to PT and OT and they were going through the paces, if you will. So those three or four hours were probably the fun part of the day. The others, and believe it or not, you started go, “well, okay, well he’s gotta sleep a little bit.” So you figure six, eight hours of that. But the rest of the day was just, when I was conscious and, and after the initial effects of the damage wore off the body. Basically, I’m awake. Thank God for NCAA women’s baseball was on TV and I got to tell you, I’m not lying, I watched every game from the East Coast to the West Coast. I just, well, I couldn’t, well, if you could imagine, I have no hands to move, to press buttons on the dial. So guess what? I’m watching what’s on. So, and I watched, typically, I watched NCAA women’s baseball until two or three o’clock in the morning.

David Naylor: And who would’ve thought there’s that much baseball on TV?

Paul Nealon: So you’d go out to the West coast and the game starts here, it’s 11 o’clock there. It’s eight o’clock. So eight o’clock game there, their time ends up at 11 somewhere. It’s now two in the morning. So I’m watching these games and game after game after game. So that helped me get through the first couple of weeks. Once that ended, it got to be, as much as there was people coming in and feeding me. So, it’s a half an hour there. My day was scheduled and there were days that I had trouble getting all my workouts in, as well as having all the other stuff because they had to bathe you and I mean, it’s not a matter of just coming in washing you. They have to lift you up with what they call a Hoyer, they Hoyer you over and I won’t get into the bathroom issues, but all that, if you can imagine somebody having to help move you on to a commode, if you will. It was very time consuming, cause you just don’t call somebody up and say, “Hey, come on in and move me.” They’re taking care of eight or ten other people and those same people are intensive care and they have needs very much like mine, if not worse, maybe a little bit less , but still. So then, they work hard and these people are, you know, the nurses and the technicians and stuff, working their tails off, trying to keep us healthy and getting better. So yeah, my day was full.

David Naylor: So through the course of this,did you always hold onto the thought that, you know, “One day I will be able to get back to some semblance of what I was,” Or was there, where there points in time where you were just like, “This maybe all that it is?”

Paul Nealon: Those first couple of weeks, I didn’t know what to think. Like I said, we had the PT and OT stuff and on top of that, my wife is coming in at 5:30 in the morning with a cup of coffee, so I could sip on that. She would literally exercise my arms and exercise my legs. You can imagine picking up somebody’s leg and moving it up towards their stomach and moving it back and 10 on one side, 10 on the other, and moving the arm around and stuff like that, just to make sure. She did that in the morning, if she came over at noon and she would come over many times at noon, she would help me with that and then at night, before I went to bed at nine or 10 o’clock, and on top of that, she’s trying to work full time, take care of the house by herself. We have a dog and just how do you do all this? But she was able to do that. So, after that, it gets to be week 3-4 and my big toe moved. Big toe on the left foot. Don’t know how, why it moved.

David Naylor: How did you know it moved? Where you able to see it or..?

Paul Nealon: No, I felt it, really all of a sudden I felt it just, it somehow, I don’t know if it flinched or whatever and you know, you’re laying there and, and I’m all alone naturally. It’s the old story. You’re all alone and you’ve got nobody to scream and yell to. Oh my God, I can’t. So I moved it and it’s like, okay. And I moved it again and I started moving it back and forth, and I imagined my whole body, the rest of my body, it’s not doing anything. But my toes moving around and I moved to 10,000 times. I kept moving and moving and it’s kind of funny cause as I did that it would send some shock waves through my body. And it was the weirdest thing. I mean, and I guess that’s a natural occurrence for people who have spinal cord injuries like that, and so that kind of was the start. So my right leg, as they were exercising, it started to stimulate other areas. So one of the things that’s on the mind, muscle type thing, the association so while they’re moving your leg or your arm or fingers or whatever, you have to be mentally thinking about that you’re doing that, that you’re actually doing the work. And somehowit tells the muscle because that signal goes down, tells the muscles to do something right and it wakes them up. At least, you know, this is my explanation. So, other parts of my body started to respond after that and we just kind of, I remember I could shrug my shoulders. That was the thing. And that was kind of…

David Naylor: Was that the next thing that came was shoulders?

Paul Nealon: Sort of, yeah the shrugging of my shoulders, it almost was easy. And that, I don’t remember what other body parts came back and it was that type of thing, but it wasn’t, hey, all of a sudden my hand moved and I could move all my fingers. It was very different parts of my body and they would come in and test me. They would test me with this swab, that little cotton swab, and they’d touch it in different parts of your body so you could feel it.

All of a sudden I could feel certain sensations, very, very light. There were times that, cause you’d have your eyes closed and they’d say, “Okay, tell me when you can feel it,” and I’d sit there and go, “I can feel it.” They’d go, “We’re not touching you,” “Well, it felt like you were.” So that’s kind of how it gradually came back and that was very encouraging, obviously. And the other thing was, they scared the hell out of you. They basically say, if you want to stay in the hospital and you want to get the most care, you have to make improvement every week, every day, and you have to really work at it. And if you don’t, we can’t justify keeping you here in the hospital.

And the insurance companies basically said, well, you know what, he’s a quad, and they’re going to turn off the lights and send him home. So that fear of losing that was probably a huge motivating factor, it’s like “Okay, I’ve got to get better. I’ve got to do something and oh, by the way, I’m not going home like this. I am just not going home like this. I can’t do this to my wife. I can’t live this way. What am I going to do about it?” And so, and I had, like you said, I had a lot of time to think about it.

David Naylor: And so, slowly you’re starting to get some sensation and things back. But there’s a huge divide between being able to move a toe and being able to stand or to be able to walk or move your arms and stuff. So that mental resilience or toughness that it had to take to be able to go through that, I can’t even conceive of how difficult that must have been.

Paul Nealon: You know what, if you had to do it, you were doing it. It’s just one of those, it’s a success thing. You sit there and go, “Okay, I had to do this before and I didn’t know how to do that. I’ll just learn how to do that, or I’ll just do it, I’ll just do it.” So the goal, you set the goal and the goal was, okay, we’re going to make Paul 105%.

And I told that to the doctor, the psychologist came in and you know, they would come in every week and asked me, “So, Paul, how are you feeling?” I said, “I feel fine.” And they said “What do you think about this?” and I said, “Well, I’m going to get better,” And they said “Well, how far would you like to get?” And then I said, that’s when I told him “105%,” and they kind of laughed and they said “But what do you wanna really do?” And I said, “No, 105% is where I’m going to be,” and so you set a goal.

David Naylor: Now, was that something that, you know, you’d been goal directed really through the course of your life, so was it kind of just a process that you’d practice so often that this was just another aspect of “I’d set goals in my personal life, I set goals in my career, and this is just one more area of my life where I’m going to, I’m going to set a goal here to make this happen?”

Paul Nealon: I have some very, specifics, around goals. At the time, I didn’t even know goal setting was something that you did. It’s like, okay, I was challenged. I was challenged, um, early on, first of all, because we were a poor family and I was made fun of. Another challenge was, okay, I’ll show you. Not in a mean way, I’ll just prove to you that I have some value. I was pretty good in sports, so as a result, I lean towards that and that carried me a long way. So success from that. So what was the goal? The goal was I’m going to have to be an athlete to have more pride around who I am and I wasn’t the most brilliant person when it came to academics. So we lean towards the sports and that worked out pretty well. So, goal setting, that I was told in my, going to Cardinal, one of the teachers, called me in and said, “Paul, you’re never going to go to college.”

Going into Cardinal Mooney, being a pretty academic school, it was like, “What makes you say that?” I didn’t ask that question. I listened to them because back then you didn’t challenge the people who were teaching you and especially the brothers that were there.

So, basically said, “You’re never going to go to college. You’re not smart enough.” Right there, I was basically, in my mind, dropped the F bomb and said, “F U, I don’t know where I’m going to be, but I’m somehow going to do that.” And I enrolled at MCC, Like I said, paid for myself, figured out how to do IT, I worked full time and worked with the school full time, which was tough. But, we got through it., you know, get a job. And then, I was told there were a couple of other things that I was not going to be able to do. And I can’t get into the specifics. It’s a little bit too, too specific. But, when those challenges are put in front of me, um, it’s just “F you, I’m going to prove to you that I have value, I’m going to prove that I can do it,” and that’s kind of what it was. It was nothing more than that.

David Naylor: Do you think that came from watching your parents and the work ethic and what they did to raise eight kids and all of that? Where do you think that strength came from to not just blindly accept that somebody says, “Hey, you can’t do this” because so many people in those, we’ve all been told at times that, you know, “Oh, you can’t do this,” or “You can’t do this,” and I can’t tell you the thousands of people that I’ve met who just blindly accept that and that then begins to define them in their lives. So to stand up and say, “I don’t care if you see me this way, its not how I see me.” Where do you think that came from?

Paul Nealon: I think some of it comes out of fear. Just a fear of letting them be right and say, “You know what? You’re right. I’m gonna lay down, I am not going to be anything.” A team, like I said, in sports, I did pretty well.

As a result of that, knew that I could do certain things. I wasn’t the dumbest guy in the room, so, you know, okay, fine. Can I do this? And through trying new things, taking that chance, opening myself up to ridicule, possibly, you know, back then, you know, you worry about what everybody else is thinking. And what if I say that I’m going to sound stupid and I couldn’t stay where I was. When you feel like you’re on the ground or the, you’re the last guy, you sit there go, you know what, “If I try anything, I’m going to be better than what I was. Even if I fail, I will have learned something from that failure. I will be that much better. I just won’t make that mistake again.” So that’s kind of, you know, the old story about practice, you know. So practicing, not being the worst, practicing and carrying that practice into hopefully success and saying, “Okay, I’m moving the arm,” and then if you get response, people will recognize something is changing and when they recognize it, they’re either challenged, they look at it and they see, “I like this,” or “I don’t like it.” They may even sit there because they are maybe fearful that you’re making progress.

They might put you down and you sit there and go, okay. I had friends who challenged me when I was going off to school. They decided they weren’t going to go to college, great and “Paul, you’re never going to get anything when you get out of college, you’re not gonna have anything,” Okay, guys. They had money, they were working jobs, and I was working, but I was paying for my own school. So it was like I didn’t have any money left over. These guys went out and bought a couple of nice cars, and I’m sitting there going, well, they got some nice cars and that, sure. Maybe they’re right. Maybe I should have gone off and worked and had fun. But yeah, you have faith in yourself. I was successful in my sports and stuff like that. School was pretty good. I didn’t study how a hell of a lot, but I was able to get through and as a result of that, sets you up for, you know, potential opportunities and success. So like I said, I didn’t have a huge area of plan and goal. But I did have that vision there. The vision of, “I’m going to show you,” and that’s kind of how it got me motivated, you know?

And as you have success with, “I’m gonna show you,” and you do show somebody, it’s like, you know what? I can do that. And that’s a challenge. Now that’s a hell of a way to go about it. But, that’s what motivated me.

David Naylor: I think, to your point and I think it’s a very valid one, that vision that you’ve mentioned is so important for people that, I was listening to something here not too long ago, and they talked about kind of the three conditions to move forward in life. You know, it starts with the vision and if people don’t have the vision that things can be better, or their state of life can be different than it is. They’ll stay in a bad state just simply because they don’t know there’s another option. And so that was the first thing. The second thing was the belief that they could actually breathe life into that vision or make it a reality. And then third, the willingness to practice, to put forth the effort to pay the dues that’s required to get there. And if any of those three pieces are missing, then they’ll largely stay exactly where they are in life.

Paul Nealon: I agree. So, I think, my parents, just the fact that they instilled in me just hard work ethics and watching my dad get up early in the morning and head off to work and head down and, you know, drove to work and came home and, you know, helped us with our studies and my alarm with my mom. He ran a tough roost. I’ll tell you when to be back in the day, you got whacked when things weren’t going right. And it wasn’t nasty whacking, it was just a paddle to the butt. But you know what? I earned a lot of those, so I felt they were justified, as much as my tail was burning vindictive. It was well earned.

You sit there and go back upstairs and go, “Okay, I’m glad that’s over with, but earned that one.” Sometimes what you did, it’s like I earned, I earned the fun. I had the fun of getting in trouble and the whacking was okay. It was justified. Yeah. That’s the way to go. You might as well enjoy it. You know, maybe I won’t do it again, but, or either that or I won’t get caught. Life lesson, you know?

David Naylor: So you’re going through the rehabprocess and you’re slowly but surely starting to gain some sensations back. So what was the, obviously the first milestone was just having that toe move and I can’t even imagine the feeling of just euphoria that something that you would so take for granted, and that’s the other interesting thing is, I mean, we very much take for granted all of the things that we can physically do, until that’s taken away and you begin to realize. So just the euphoria of being able to move your tow had to be, I can’t even imagine what that had to be like.

Paul Nealon: When you hit it, you know, like a hole-in-one. You’re up to par three and you’re ready and hit the ball and it goes in and I’ve never had a hole-one but I’ve envisioned, you know, and maybe someday I will. But there’s nobody there to tell. It’s like being with your wife and looking at a beautiful sunset that you’ve never been in Jamaica, for example. You’re looking out and you go, isn’t that beautiful? But seeing it alone, you can think, “Well, it’s beautiful, but I wish there was somebody to share it with.” That was the euphoric thing that I’m sitting there going “Oh my God, I can’t believe it,” I’m yelling, I’m in my room and I am looking around, the door is closed to my room. I was going, “Oh, F, nobody can hear me,” you know? When my wife came in a couple of hours later, I couldn’t even get it out of my mouth, but it was exciting and it was exciting for her, because guess what? There was hope.

David Naylor: And that’s so important. So you’re going through the rehab process, which it had to be just overwhelming trying to go through, so slowly but surely you’re starting to see things come back. You’re getting sensations in different areas.

So at that point was it just, did you focus on one arm at a time or was it, how did you, how did they kind of..?

Paul Nealon: Yeah, we didn’t know what was coming back and when it was going to come back

David Naylor: Or even if..

Paul Nealon: Over the coming weeks and almost on a daily basis, something would, you know, it might be just that I could actually feel my leg. When somebody moved it, I could feel that it was moving. If you could imagine, one of the things that happens is that you had this sensation where you may think that your hand is laying across your stomach, where in fact it’s laying on your side.

It’s just, I forget the term, but there’s a term for what that is. So you could think that you’re touching your nose and your arm might be down, touching your leg and it just, it doesn’t, it’s just a lack of association. The body doesn’t know where things are.

But as they came back, I would just obviously tell people and we would work on those, but you just never knew what was gonna come back, and it wasn’t a matter of, “Hey, my arm is moving,” therefore my hands were moving. It just came back little by little.

As they tried to do, you know what, they were actually trying to get me to walk. What they do is they suspend you from the ceiling and you’re in this harness and they basically take all the weight of your body and put it into the harness and you’re hanging there, if you will. And then they let your legs kind of like, and I’ll say drag and they actually have a walker that you’re supposed to put your arms in and use, but I couldn’t grip on to things. My grip was starting to come back and my left hand, but my right hand and my right side was more severely impacted by the injury. That was understood as they watched me get better, if you will, they could say, “Okay, that makes sense. He was more damaged on the right side than he was on the left and the spinal cord, therefore the left side is going to respond a little bit,” and that’s kinda how it went down, but you could never associate one with the other. So I’m kinda being suspended from the ceiling and they’re trying to walk me along and it’s like, okay, because I can now kick or move my leg, I can almost move it in a walking position and put it out in front of me, but I couldn’t feel my foot when I put my foot down. I would see my foot on the floor, but I couldn’t feel it being on the floor. So they kept, “why do you keep looking down?” And it’s like, “Because I can’t lean forward into it because I can’t feel that my foot is supporting and my leg is supporting me on that step.” Therefore, you have to start, you’re just looking down, you know? By stimulating some of your muscles by leaning into them and doing so, it’s…

David Naylor: So, you just have to very cognitively, I mean, we walk, we don’t think about walking anymore, but for you, you had to be very cognitive.

Paul Nealon: Total concentration. When I was done with the physical therapy, when I was done with that, I was mentally probably more mentally exhausted that my body was physically exhausted, it was just incredible. But the payback was huge. So I was lucky, I got feedback relatively quick over a number of days and weeks or whatever. But then things started to move and you could put more complex movement into it. So not only am I trying to hold my body upright, but I am now moving my leg forward. I’m lifting it up and moving it forward. Now I’m putting it down and I can’t feel it. So there’s the mental side of, okay, trust, right? Trust that it’s there. Trust that it’s gonna hold you up. Trust that your muscles within your quad and your knee muscles in your calves are all gonna engage at the same time to hold you up.

The body has to learn that again. The whole, the sequence, the computer in the brain all has to be told, “Guess what? You’ve got to do these things together to hold him up,” and that’s kinda how I thought about it. You know, if you really think about, okay, what is the body doing? It’s kind of like bodybuilding, you go, okay, we have to confuse the muscles. I, having worked out for 45 years, you sit there and go, okay, “I know I can build muscle,” it’s just a matter of, it’s going to take some time. And oh, by the way, the muscles of atrophy feed to the point where there’s so much atrophy that, I can’t hold my body up, but I know I can make muscle.

So what’s the goal? The goal is to make muscle. Do I know I can do it? Yes, I do. I’ve done it in the past so. I call that, you could call that practice, and it might make a muscle. How do you do that? Just go through the motions and strain it and work it. Think about sending the muscle that message from the brain. And if you don’t send a message, the muscles not going to do any work. And if it doesn’t do any work, you’re not going to get any better. So it was really that basic.

David Naylor: So kind of just breaking down in your own mind, what is exactly the process that needs to happen here? And then physically creating that association again.

Paul Nealon: That was really mentally exhausting and then you get back to the bed and you’re laying there and there were people are coming to visit me and I’m dozing in and out, and it’s not because of the drugs, it’s just, you know, you’re tired.

At the end of the day, I was ready for my, I call it the cocktail. My cocktail was a number of drugs before I went to bed. They had different things that would knock me out, which was good. But when I woke up, I would be, I was like a brick. Early on, I was a solid, every morning, a solid brick and that went on for at least a…

David Naylor: So by brick do you mean like, stiff?

Paul Nealon: Well, if you could imagine you’re just a head laying on a bed and most of your body is not moving at all. You can’t move much of it all. You’re just starting to get some sensation back. That’s probably the hardest is that you wake up in the morning and and the drugs were drying me out to the point to where my mouth was sealed. I was sealed shut. I mean, it was like somebody put glue on it and I would wake up in tears. I mean, I, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t move to call anybody. But I knew they were coming at six o’clock, because I was being cast every six hours.

So I knew at six o’clock they were coming and as a result of that, I knew they were coming and it was like, I’m laying there and my body would be and the medicine was wearing off, so I was in total pain. And you sit there and go every morning. It was, you know, every morning was Groundhog’s day every day. You wake up in the morning and you know, here I am and I’m thinking every day, every morning, “How am I going to endure this pain and how am I going to do this and when is it going to end where I don’t have to wake up with my mouth sealed shut?”

When they got to me, they would, you know, unseal my mouth, pour a little water in it. I would choke a little bit and then I would be able to start to talk, and then I could finally say, “Could you get me some water?”

David Naylor: Sohow did you not lose hope in all of that?

Paul Nealon: Boy. I said this to you, but I think before, I’m just not smart enough. I really, I don’t give up. I’ve never quit. I think I’ve never quit, no matter what it is. For some reason, I think that I can get through it, pain, early, you know, maybe it’s being bullied when you’re a young kid, people are laughing at you and stuff like that and you get through it.

You say “Okay, I survived that, so why can’t I survive something else that’s maybe just as bad?” At that time, that felt like it was the worst and it was at that time in my mind, but this was worse or the worst of the worst. I don’t know what drove me to think I could do it.

But past experience said “You’ve been successful at all these other things. Why not at this now?” I hope the body comes along with it. I didn’t know, I didn’t see any x-ray. I didn’t see anything say, “Well, Paul, this is where it was all screwed up and you know, this is where we fixed you,” so I did see the apparatus they put in my neck to fuse everything. But it’s like, okay, that’s mechanical side. What about the rest of it? I don’t know what, just past experience I can say.

David Naylor: Yeah. Just pure belief and a refusal to accept anything else.

Paul Nealon: By the way, you know, I am not being a religious guy. I said a couple prayers, and I made a couple promises to whoever is out there. If there’s a guy out there, and I’m still trying to find out if there is or not. I know a lot of people sit there, go, well, you know, how could you, you know, there’s the atheist, then there’s all the ones lined away. I don’t know. I don’t know what the answer is. My parents are very, very religious people, tremendously religious people.

I don’t have that deep belief, but I, you know, it’s the old story with, you’re in a foxhole and you’re getting bombed. You know, you’re sitting there going, “Dear Lord. Please help me. And if you’re out there, if you’re out there, I need your help and I need it now,” and I basically said that, I’ll just tell you, I made one promise that I can, I can share out the other ones, that if I could get to where I am today or even close to this, maybe not even close to where I am today. I will go out and I will talk about God and I will not be ashamed to talk about that I believe in him and that he’s out there. I’m trying to find out if there really is one. I just am not convinced that there is, or there is not, but you know, I’m not taking any chances, and I’m not gonna say the guy doesn’t exist. Maybe I’m going to need him again. And maybe he does. And maybe he’s going to sit there and bless me.

So then maybe, I’ve talk about being blessed. I’ve been blessed with all the people around me. The people that, I mean, my wife, my God, I can’t say enough about what she has done, top and bottoms, and this happened. I mean, I don’t think I could ever do what she does and she does it willingly, lovingly. She gets mad at me, but I deserve it. Probably. But God, I couldn’t be where I am today, if it wasn’t for her. My recovery is mostly, and I say is mostly because of her, because if she didn’t give me the ability to go to the gym every day, basically she said to me early on, “The only thing I want you to do is worry about getting better and getting better so we can have a life together.” That to me was like, I can’t ask for it. And she’s lived up to it. Every day, I go off to the gym, you see me over there, I go off to the gym, I come home and I’m spent, I’m dead. I drag my butt out of that gym and I come home and I plopped down in the chair and she’ll see me when she walks in.

There’s Paul again, sitting in the chair. But I’ve done what I could do and I get up and I try to make dinner every night. I do make dinner every night, that’s part of my physical and occupational. I try to do the dishes. I try to put dishes away. I tried to take them out of the dishwasher.

Those are all the physical things that I still have to do to do more things, to get where I need to be. Those are things, but going back to Claudia, if she’s not here, I don’t know that I could be where I am today. Its one of those things, I sit here talking about it right this second.

I’ve appreciated her and told her a thousand times, but really, I look at it and go, I’m lost for words. She’s the reason I’m where I am and she’s the reason I’m going to be where I’m going to be. I don’t have to worry about anything. She’s going to be there for me. So, yeah.

David Naylor: Hmm. That’s phenomenal. So Paul, going through this journey, and I remember hearing about the accident and I was at the gym and one of the guys that you and I know in common told me the story, and I was floored.

I was just shocked. I couldn’t even put it into words. And so it was, and periodically you get updates from people at the gym about what was going on and those kinds of things and here’s some of the good news and you’re just hopeful that things were progressing.

I’ll never forget the day, the first day I saw you back in the gym and you’re haltingly walking through the gym and you and I were talking and you’re kind of explaining to me the journey of what you’d been through, where you were at that stage.

I remember you said to me that, I think we were talking about walking and you, and you said, you know, “When you walk, you just walk, you don’t really think about it. if I don’t think about the fact that I got to lift my foot up, I’ll stumble,”

So you have to think about each little phase of what it took to walk, to kind of put the sequence together. So phenomenal journey to come back to where you are now. I love the 105%, because you can’t come through a journey like this without being mentally better for it.

Paul Nealon: Yep. But that’s where the 5% comes from. I had this vision of myself and I still do the old Paul, the Hulk, and all of a sudden the Hulk is now a blob and doesn’t have much, cause I placed a lot of meaning in what I looked like, and I took a lot of care in my body and stuff, and all of a sudden that was stripped away. It’s gone. I had to make a decision, what am I going to be because I’ve got this block now, I don’t know if I can get back to where I want to be or the 105%. I’m going to take that journey. Yeah. But I don’t know where it’s gonna take me, but I have an opportunity. I have an opportunity to make it different than it was before. Now I still say this, Paul, see this old Paul, I want that body. I want that body back and I’m going to somehow get it. I’m convinced of that. I don’t know how long its going to take. I’ve got a little age working against me. You know, people will say to me, you know, “Paul, you are getting older, so, you know…”, and, bullshit. Age has nothing to do with it. I mean, there are guys who are 80, 85 years old, and I see them lifting more than I have. So guess what? I’m going to get that body back. So, or at least I’m going to take the journey and I’m not afraid to do it. Now that people are, that to me is the challenge when somebody says, guess what, age has got you. Guess what? That’s a challenge. That’s telling me my age is now saying, I can’t do this. Screw you. I’m going to do it. So where did that come from? I don’t know, but the blob is going to be something that’s not a blob forever.

And then he will have learned a lot more along and sharing this journey with other people is one of the promises I made to whomever that person is, I’m going to make this valuable to other people. I don’t see myself as being a person who really is a deep thinker.

But I am going to share my encouragement with anybody that I can, and I’m going to encourage other people to look at people that are like me now, or that have disabilities to be open and to ask somebody how they’re doing. How’s that guy who’s coming out of the wheelchair? when you’re on the elevator and you’re the only one there with him and he’s in a wheelchair. “How you doing?” you may not want to say, “Hey, what happened to you?” but that person sitting there and they’re feeling a lot less than you are. You’ve got the whole body. I don’t have the whole body and I’ve learned how to feel that way.

I’ve lived with those people and I’m one of them and I want people to say, “Hey, how you doing?” I’m lucky enough over at Midtown, everywhere, I walk into that gym just about every day, if not every day, not just one, but several people come up and say, genuinely, “how are you doing?” Or, “I read your story,” or “I heard about you. How did that happen?” I’ve told my husband to stay off that ladder. Now, we hire somebody to do the work because they’re professionals and I don’t want my husband up there. He’s X amount of years old. He doesn’t belong up there.” Those are the things that say, okay, this is a worthwhile journey.

I’m going to use it for what I can, not for me. I got an opportunity to express and help others, and actually, I’ve been blessed to talk to people down at Horseheads down in Jacksonville, Florida. I met a guy down in Jacksonville, Florida, who was in a car accident and was sitting in a wheelchair and I actually was talking to them and my wife said to him, “You know, Paul had a fall and was like you about a year and a half ago,” and he looks up at me and he goes,” I could be like you?” And I said, and he was 33 years old and I go, “Well, yeah, I don’t think you want to be like me because I’m 69 but (67 or 68 at the time) do you lift weights? And he said, “No, I’ve never lifted weights before,” and I said, “They’re right over there. They’re right over there,” and I pointed to them, I said, “You’ve got to lift your weights, you’ve gotta get your muscles going. I’ve lifted for a long time and I swear by it. And you’ve got to do that if you want to get out of that chair,” and my understanding is he’s now walking, I understand he’s gone back to work. So did I have anything to do with that? I tried to encourage him. He thought, and his parents were there at the time and they look and then, like you said earlier, Dave, when you look at me now, you sit there and go, well, okay, so he walks a little funny and he drags his leg a little bit, but you wouldn’t sit there and say he was in this condition exactly a long time ago. So I understand why they look at me, but that’s hope for them. It encourages me, it makes me feel as though, you know what? There’s another challenge I have to prove to these people. That I can do it, that I can come back. Cause I told them I’m coming back to 105% so I’ve got something that I have to attain because I’ve been shooting my mouth off that I’m going to get 105% it’s the old story where you know I’m going to lose 20 pounds and you tell enough people, you’ve got to do it. So it’s not bad to get out there and tell some people that this is what we’re going to do. So if you’re, I don’t know, running a company, this is where we’re going to go, start talking about it, you know, get it going. To me that’s, you know, if people think you believe it, then they’re going to start to believe it. And when they start to see you doing it, its, you know what? Maybe this is where we’re going to go. You know, it was a crazy idea, but guess what? We can do this. And that’s, you know, look at the teams of sporting teams that are crummy in the last play. What was st Louis like? Look at st Louis blues. Just last year, my god, last place. Worst team. All of a sudden, Stanley Cup.

David Naylor: Wow.

Paul Nealon: Somebody started believing.

David Naylor: That’s exactly right.

Paul Nealon: So, whatever.

David Naylor: So Paul, let me ask if you had to share with, you know, the folks that are listening, the greatest lessons that you’ve learned from shattering, you know, four vertebra, being paralyzed from the neck down and the battle back. What would those lessons be? What have you learned through the journey?

Paul Nealon: Well, I think, you’ve got to take that first step, right? I mean, you know, we talked about it before. My belief is you can always do one more, one more curl, one more. At least try to pick up the leg. You may not be successful on that first lift, but talk about practice, practice gets you into the game, right? So you do the practice. So all the work before, take that first step, you fall down, you get back up. The life lesson, I mean, we all talk about, you know, take the first step. That first step is so challenging because of the fear of failure, fear of being made fun of, a fear of other people thinking less of you and we have talked about before. They’re so busy worrying about themselves that chances are they’re not worried about you falling down. Yeah, it’s funny for five seconds, and then, you know, you try it and guess what? You don’t fall and the next foot goes out. So, life lessons, you know, set the goal. You know, believe you can do it. You can always do one, one more. And that’s amazing. As you’re doing a sit up and you get to number 10, don’t stop at number 10.

If you can do 12, do 12, but you get the 12, you go, you know what? “I’ve got another one in there,” and just try to get it. But you don’t get the 13. But you got halfway up there. Well, the next time you try, or two or three days, when you try again, you’re going to get 13.

That’s kind of, all you’re doing is building on it. So it’s a little building blocks. It’s all the things we’ve talked about since we were a little kids. It’s starting off and just building on. Little successes, you know, hitting a baseball, you know, it comes in faster and faster from the machine and guess what? You get picked up with the, “I know I can hit the ball,” so you’ve got to believe it. I think you’ve got to believe in it. But, you guys are very successful. You started a business. Well, how are you going to get it going? It’s just you and your partner. And all of a sudden it’s like, “We’re going to do something. We’re going to be successful and the goal is this because I like doing this and I’m good at it, and I have to go out and I’m going to have to create a product, sell that product. So I’ve got to believe that it’s the best product out there and if I can do that, I now have confidence in what I’m selling, so I just got to get somebody believe that this product is as good, if not better, than when I say it is. Then I got to back it up.” So that for me is okay, my product is okay. The 105%, I’ve got to produce that, and then when I get there, I’ve got to go out and do what I just said I was going to do, help others in any way I can. So, we’re going to do that. It’s going to be pretty simple.

Just go out and have people talk to you and encourage you. I get so much encouragement and as a result of that, it just makes me want to help other people. It’s not one of those things where you sit there and go, “Oh, it makes me feel so good,” well, it does feel good, I’ll tell you that.

But it’s not what I’m trying to do and it’s not my intent. So sitting here today really is to hopefully share my story, to encourage others to take that first step. It only takes one. If you believe that challenge, don’t let fear stop you. Fear is one of the things that, there’s the fear of success or fear of failure, one or the other, you know, or pain that, you know, we talk about, pain and gratification and what’s worse? Pain is horrible. Success feels great, you know?

The pain, our fear of not doing something, if you let that sit there and stop you from doing something for the pain of that temporary situation where you sit there and go, guess what? I failed. And everybody’s laughing at me. Okay, try it again. Try it again. And keep doing it.

We talked about being a musician and they don’t build out the song right away. They don’t play the guitar right away, perfectly. They probably hit some bad notes and that success that they had comes over many years of hard, hard, hard work. But the belief that “We’re going to have a good product here. There’s going to be a good song that’s going to come out of this guitar, whatever it is, trombone. As a result of that, I’m creating, but there’s a lot of bad notes along the way.” But it’s the belief thats there. And once you’ve got that, I just think, you know, then it’s off to the races, you know?

David Naylor: Well, and I think your points exceptional, you can always do one more. And if you had that philosophy just like 105%, you have that philosophy and if you stay focused on that consistently enough, over time, you’re miles ahead of where you started with and don’t be ruled by the fears because we all have them.

Paul Nealon: Oh, you know, it’s, I guess as you get older, you start to accept the fact that you will fail. It’s embarrassing, but it’s not as embarrassing as it was when I was 18, when I was nine years old and somebody was making fun of me. It’s not, you learn to accept it and say, you know what? I lived through that. You know? And that’s what, because you lived through it, it’s like, okay, and it happens again.

It happens again. We all do stupid things. We all step in the mud. We get food on our clothes. I do it almost every day. I’m “Mr. Mess.” I call myself “Mr. Mess.” I try not to, but if after a while you start to go, you know what, I did it again. I spilled on myself.

And you can point at that and make fun of yourself. And, and people sit there go, well, yeah. And then they all laugh and stuff, but we’re all laughing together. And it’s not laughing at me, we’re kind of laughing and you feel comfortable about it. So if people can accept the fact that they will fail, but taking that one more step, it feels so much better when you’re successful by taking that step and putting the next foot in front of that. That’s like two and three steps or now you know where I am today, walking as well as I can right now, but I will be walking better soon.

David Naylor: That’s all anyone can ask. Well, Paul, thank you so much for coming in and sharing some time with us today. Your story is a phenomenal one, and I think the lessons from your journey are lessons that all of us can benefit from. So, very much appreciate you coming in.

Paul Nealon: You’re very welcome. It was a nice sitting down with you and Sean. I didn’t know that it was going to be so simple and that I could share as simply, and it helped me, you know, get a little bit out of my mind and brain here and be able to speak a little bit around it cause sometimes, you have the thoughts but you don’t put them into words. So it gave me an opportunity to kind of share and hopefully help anybody and by just the, this little podcast that we’re doing here today, if there is anybody that I could help in the future, you know, my numbers and they could get ahold of you and I would do anything and go anywhere to help them out, do something online. I’d be very thrilled to help anyone along the way cause I’ve got some ideas that I think I could share and encouragement I think I could share as well and hopefully help anybody that needs anything, whether it be a physical injury or some mentally impaired or there’s just a lot of things out there that you never know when people are going to come and tap you on the shoulder and say, “could you talk to this person?” I’ve been lucky enough to do it already with several people and hopefully just added a little bit of a hope to their future endeavors and how they get better and handle their life moving forward. So I’ll leave it at that.

David Naylor: Of course with everything that you’ve gone through, obviously there was a tremendous support system that you had at home. You talked a little bit about the difference that, you know, Claudia had made and how you wouldn’t have been able to make it through without her support and I’m sure there were countless other people that really made a difference through the course of the journey. So, who are those people that really made a difference?

Paul Nealon: Well, Dave, thanks for giving me the opportunity to be very personal in this point because I just cannot end this interview and podcast if I didn’t really call out all the people that were so instrumental in my recovery and my continued recovery.

So first of all, as you mentioned, Claudia, her past and continued care, I cannot say enough about her devoted love and support. What am I going to do? I mean, she’s just everything. Then there’s the lady across the street, Sylvia Park, my hero, as I call her. She had the courage to investigate the noise that happened at that fateful day, May 20th.

I’ll never forget her and without her quick action, my life would have ended that day. Then there’s my children, who I tried to, as I mentioned, I tried to get ahold of them. I couldn’t get ahold of them, but boy, did they come to the rescue for the next five months. When I was in the hospital, they showed up every week.

Kelly, my daughter, would travel home from New York City. During the weekend, she would stay through Monday. Sean would come in on Tuesday through Thursday or Friday. And that went on for several weeks. I think it was almost five months that they adjusted their work schedules to be able to take care of me.

On top of that, they support Claudia in all that activity of trying to keep the house going. Just keep things in some semblance of order, if you will, while I was incapacitated. Then there’s my oldest son, Chris, who lives in Austin, Texas. A very busy schedule, but boy did he call all the time, checked on me all the time, flew home and even, I mean, he used his vacation days.

He did, and he doesn’t get much vacation time home. So if I could just thank my immediate family, I can’t say enough, my parents, my brothers and sisters, my immediate family, my cousins, everybody that showed up. They visit me to send cards, my friends, my God, I never realized how many friends I had, over 400 cards that I received.

I got cards from people that I don’t even know from Italy, um, sisters of Saint Joseph, praying for me. And I mean, just, it goes on and on and on. So I can’t really thank people enough. I am blessed. I am blessed to have each and every one of them. I just thank every one of you for your support and you are the reason for my continued improvement, I will not fail you. Here you go. Thank you so much.

David Naylor: Thank you, Paul.

Paul Nealon: Dave, thanks for the time, Sean, thanks for your time today. A lot of help is going to go out to some people. Hopefully we encourage them and give them the help they need. This was a blessing for me. Whether I want to, I have to look at it that way and appreciate everything you guys have opened up for me, cause I know this is gonna just be the start of new opportunities for all of us. There you go. Wow, thanks.

David Naylor: Well, thank you, Paul.

Paul Nealon: Sure.